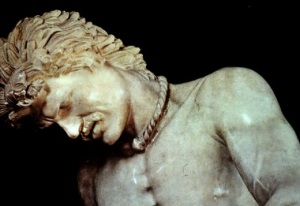

The Dying Gaul

I was touched as I have seldom been by a work of Art. The face looking down at me was not at all the ‘noble countenance’ one reads about but, on the contrary, a face so ordinary that its wearer would not have stood out if he had walked our own streets: unkempt hair, low forehead, slightly snub nose and a Celtic moustache of the type that has for some time been back in fashion. The mouth is half open and the features are frozen in an expression less of pain than of painful bewilderment.

- Gerhard Herm from his work “The Celts”, on his viewing the Dying Gaul at the Roma Capitale

The consensus on the origins of the “Dying Gaul” is that it is a marble copy of an original bronze sculpture commissioned by the King of Pergamum to mark the defeat of Celtic Galatia. The Greek bonzes are thought to have possibly been brought to Rome in the reign of Nero where a marble copy was made and it is this copy that was unearthed in the 1620’s during an excavation at the Villa Ludovisi. By 1736 it was on permanent exhibition at Rome’s Capitoline Museum where it has remained except between 1797 and 1816 when it was at the Louvre after Napoleon stole it and took it to Paris.

The Celtic World of the 3rd century BC was vast, an area of Celtic dominance that stretched from Ireland to the Black Sea and from Central Europe to southern Spain in an arc of Celtic cultural hegemony. A glance at the maps of the period show a curious enclave of Celtic political and cultural dominance located in what is now central Turkey, and isolated from the wider Celtic world. History has named this enclave Galatia.

Galatia was the subject of a 2001 New York Times article which focused on recent archaeological findings. Confirming the existence of the Celtic state of the same name, the article cites a scholarly study published in the British Journal of Anatolian Studies as follows:

...the Galatian communities established in the third century BC constituted ‘a new, significant and increasingly important geopolitical entity within Asia Minor’ and this ‘can hardly be attributed to a marginal and politically, socially and economically unsophisticated people. The fact that their polities survived to be incorporated into the Roman Empire would indicate the existence of highly developed social structures bound together by shared value systems.

Barry Cunliffe in his seminal 1999 work “The Celtic World” describes the retreat of a disorganised mass of Celtic warriors from an ill fated incursion of Greece around 275 BC. At the invitation of a Greek prince who wanted to use the Celts against his rival kingdoms, three tribal groups numbering perhaps 20,000 broke off and crossed in to what we now call Turkey eventually establishing Galatia, the easternmost area of Celtic settlement. Galatia was a vibrant, short lived and prosperous Celtic state. Galatia’a neighbour, the Kingdom of Pergamum, one of the successor states to the empire of Alexander the Great, made short work of Galatia and it is the image of the Dying Gaul that dates from the conquest of Galatia by its Greek neighbour. Eventually, in around 88 B.C. Rome arrived, sacked what was left of Galatia and began the steady integration of Galatia into the Roman Empire. The name lived on in the Roman province of the same name and scholars point to evidence of the Celtic tongue surviving in central Turkey until the late empire. According to the Times article,

..St. Jerome (who lived in the 4th century A.D.) observed the Galatians used a dialect similar to one spoken in the Gallic town of Trier (in Gaul), back in the Europe they had left in the third century B.C.

One of the first things noticed when viewing the powerful image of the fallen Celtic warrior is the Torc, or Torque, around the neck of The Dying Gaul. The Torc is an emblematic piece of jewelry associated with Celtic civilisation. Time and time again the Torc has been unearthed in troves of Celtic artefacts and pictured being worn by figures in bronze and stone associated with Celtic settlement. The Torc, an undeniable marker of Celtic culture persists to this day. Just look it up on the internet and you can get one for yourself. It is startling to think that this symbol of Celtic identity binds us still. Here is the representation of a fellow Celt in his death throes 2300 years ago and he is wearing a piece of jewelry that proclaims his Celtic identity that we are still wearing today.

From the University of North Carolina we have the following description of the significance to the Celts of the of the Torc:

Poseidonius (Greek Historian) describes the Celtic peoples’ "delight in gaudy ostentation" that is best exemplified by elaborately decorated, impressively thick and heavy torcs. The torc, also spelled torque, is a ring of twisted metal that the Celtic peoples typically wore around their necks, waists, arms, or across their breasts. In sculpture and in painting, the torc - the "archetypal personal ornament of the Celtic world" - has become a means of identifying a figure as Celtic. For instance, the Dying Gaul, the most well-known Roman depiction of a Celtic warrior, wears a torc around his neck. The Celtic god, Cernunnos is depicted on the Gundestrup Cauldron with a torc around his neck and a torc held in his hand. Ancient writers, like Poseidonius, mentioned the distinctive torc of the Celts; the Greek historian Polybius wrote of the Roman troops’ fear at encountering the Celtic warriors who were "richly adorned with gold torcs and armlets." The torc would have been known to Egyptians, Persians, early Britons, and Romans through monuments and Celtic coins as the signifier of a Celt and as an impressive symbol of strength and power. Archaeologists have found torcs of different metals, sizes, shapes, and decoration throughout the lands in which the Celts once lived. The (Celtic) mythology reveals how Poseidonius’ description of the Celtic love of ornament is simplistic; the Celtic peoples not only enjoyed beautiful ornamentation, but also shared a mystical belief in its powers.

The Dying Gaul on Display

The statue is on permanent display as part of the Capitoline Collections in Rome. Copies of the Dying Gaul can be seen at museums around the world including the Museum of Classical Archeology at Cambridge University, Leinster House in Dublin, and at Museums in Berlin, Prague, Stockholm, Versailles, Warsaw and several locations in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Further information

The Celts, by Gerhard Herm: 1975 – St. Martins press

Atlas of The Roman World, by Tim Cornell and John Matthews:1982 – Facts On File

The Celtic World, by Barry Cunliffe:1979 – McGraw Hill

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/25/science/archaeologists-find-celts-in-unlikely-spot-turkey.html

http://www.unc.edu/celtic/catalogue/torc/Torcs.html

- Pan-Celtic

- English

- Log in to post comments