The Fight To Save The Irish Language – Interview with Seán Ó Cuirreáin – Ireland’s First Language Commissioner

Transceltic are honoured to have had the opportunity to interview Seán Ó Cuirreáin, Ireland's First Language Commissioner. Mr Ó Cuirreáin announced his resignation in December 2013 in dramatic testimony before the Irish Parliament's Joint Committee on Public Oversight and Petitions. During his final appearance before Parliament earlier this month, the Commissioner stated his decision to resign was promoted by the failure of the current government to support the Irish tongue:

For those who believe in language rights for Gaeltacht communities (Irish Language Area) and for Irish speakers in general, this is a time of great uncertainty. We have two simple choices – to look back at Irish as our lost language or forward with it as a core part of our heritage and sovereignty.

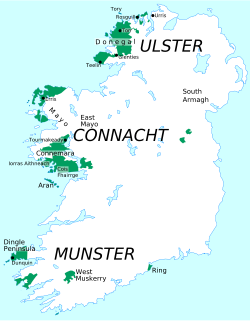

Seán Ó Cuirreáin was appointed Ireland’s first language commissioner by the President of Ireland in February 2004 on the advice of Government following resolutions approving the appointment in both houses of parliament. He was reappointed in a similar manner for a further 6-year term of office in 2010 but announced in late 2013 that he would stand-down from his position on 23 February 2014 when he would have completed 10 years as commissioner. He is a native speaker of Irish, born in the Donegal Gaeltacht in the North West of Ireland. A graduate of University College, Galway before his appointment as commissioner, he had previously worked in journalism and broadcasting, primarily in news and public affairs. The commissioner’s office functions as a compliance agency and ombudsman service in relation to Irish language issues under the Official Languages Act 2003. The Irish language, spoken in Ireland for nearly 2,000 years, is one of the oldest written languages in Europe which still survives as a living community language. As well as having official status in the Irish constitution, the Irish language is also recognised as an official language of the European Union.

Interview with Seán Ó Cuirreáin – Ireland’s First Language Commissioner

How do you see the future of the Irish Language?

We are at a crossroads in relation to the future of the Irish language. While there is no doubt that the language will survive, the more important question is whether or not it can survive as a living community language – the dominant and commonly used language of people in Gaeltacht (Irish speaking) regions. Of course, the last native speaker of Irish hasn’t been born yet and people will continue to speak and write the language – but will it survive as a community language? This is altogether a more challenging matter. I believe that the language will not survive in Gaeltacht regions as the living language of the community unless it has national status – that it can be used with ease in courts, parliament, and with state agencies. And it will have less relevance on a national scale if it does not survive in Gaeltacht regions as a community language. Both issues are directly interrelated.

The “20-Year Strategy for The Irish language 2010-2030” sets a goal to increase the number of speakers who use Irish in daily life from a 2006 base line of 83,000 to a target of 250,000 in 2030. What actions need to be taken to meet this objective?

I always felt that target of 250,000 was arbitrary and had no coherent basis in planning. In fact in a commentary in July 2008 during the preparation of the strategy I said “I understand that the objective of the strategy is to have 250,000 people speaking Irish daily in twenty years time. This is, without doubt, an ambitious challenge, the achievement of which will require an annual incremental increase of 6% from the current level of Irish speakers, year on year, for each of the 20 years. It also requires that at the end of the 20 years, the number of people speaking Irish on a daily basis will have increased 350% from the present level.

On the other hand, there are over 450,000 people who stated in the 2006 census that they use Irish on a daily basis within the education system but who don’t use it at all outside that sphere. If the strategy could assist in influencing some of this group to use Irish more frequently, on a daily basis, it would be a significant achievement in this project." Even if all of the actions and measures promised in the Strategy were being implemented, the figure would have been very challenging. I think with the experience of the past 3 years (the first 3 years of the strategy) behind us, it would be difficult to find anyone who would suggest that the target is in any way realisable.

The Irish Constitution declares “The Irish language as the first official Language”. Can you help Transceltic readers understand the factors that have led to the current situation given the constitutional guarantees enjoyed by Gaelic. How would you characterise the level of Irish Language services provided by the government to Irish Speakers?

Constitutional status, while very important, is merely the broad brushstroke and legislation was required to give effect to that status. It took 80 years of independence for the State to introduce the Official Languages Act. So, while the status was always there, the rights that it conferred on citizens were often worthless as no legislation was introduced to underpin those rights. Occasionally, citizens had to take constitutional cases to the courts to seek their language rights before the introduction of the 2003 Act. The level of service provided by the State through Irish is relatively low with a minimalist approach being adopted by many state bodies. Often services in Irish are provided reluctantly, and are of an inferior quality or are delayed compared to services through English. Few Government agencies attach a high priority to the supply of services through Irish.

Given the apparent failure of the Irish government to fully support the Irish Language, what role do you see for non-governmental organizations, such as The Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaelige), in supporting the tongue?

All of the non-governmental Irish language organizations have a role as advocates for the language, making a case to the authorities for the promotion and protection of our national language. They are often the voice of the Irish speaking community and should be seen as partners and stakeholders in the efforts to ensure the language’s survival.

The Good Friday Agreement resulted in the establishment of the Foras na Gaeilge, the body responsible for the promotion of the Irish language throughout the whole of Ireland. What do you see as the long term role of the Foras na Gaeilge in the future of the Irish language?

Foras na Gaeilge is in fact the main-state agency for the promotion of Irish not just in the 26-counties of the republic but for the whole island of Ireland. In an ideal world an Foras should be to the Irish language what Fáilte Éireann is to tourism promotion or CIÉ to public transport. In other words, it should be the agency which would assist government agencies to improve their level of service though Irish and crucially would focus the state’s actions and energies on its responsibilities in the promotion of Irish.

In your final address to the Irish Parliament you stated that “notwithstanding those within the State sector who support the language, there are stronger and more widespread forces in place that have little or no concern for the future of our national language”. Can you please clarify the meaning of your statement?

If you regard public administration as having two sides – the elected political masters who should decide on policy and the executive or administrative element (civil or public servants) who implement it, I was suggesting that there is a large cohort of people within the state sector (mainly senior civil servants) for whom the language has no importance nor is it anywhere on their agenda. The politicians are generally favorable towards the language but very often too caught up with what they would see as more important issues (such as the economy, finances, etc). The civil servants, occasionally referred to as the permanent government, hold much sway and can set the agenda in their own way. While there are many who are favorable to Irish and concerned about the language’s future, there are many, many more who simply regard anything to do with Irish as a thorn in the administrative side. The culture of any organization seeps down from the actions of those at the top and if the view from above is that the language is not important this sets the trend and agenda with state agencies’’ staff.

For further information, please see: www.coimisineir.ie

- Irish

- English

- Log in to post comments